Design. Origin Stories.

When design starts, according to whom

I am a designer first and foremost. Not a historian and not a researcher. But as a designer I have always wondered about the origins of design. Over years of reading I realized that the “start” of design depends on how you define both the word and the activity of designing. Another recurring issue: design history is often folded into the histories of architecture, fine arts, and craftsmanship. Depending on who you read, you will see different dates set as the beginning of “design.” In this article I summarize the most frequently cited origin stories.

Renaissance Italy: disegno as the birth of design

One strong claim says design begins in Renaissance Italy, when planning and drawing split from making. Before that, in artisanal practice, the same person usually designed and executed the work.

Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) is the pivot here. In his treatise De re aedificatoria he defines lineaments as “the precise and correct outline, conceived in the mind,” and says you can “project whole forms in the mind without any recourse to the material.” He also draws a line between the person who designs and the person who builds, calling the on-site craftsperson “no more than an instrument to the architect.”

Modern historians explain the shift in plain terms. Mario Carpo puts it like this: “the Albertian architect does not make buildings; he just makes drawings of buildings.” Drawings become instructions. Others build from those instructions.

A little later Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) gives this idea a name, disegno, and ties it to the three arts. In the preface to the 1568 edition of Lives of the Artists he writes that disegno is drawing understood as intellectual conception, “originates from the intellect,” and is the “father of our three arts, architecture, sculpture, and painting.” With Vasari, a working term used by artists becomes a public principle: design is the mental act that precedes and organizes making. In 1563, Florence founded the Accademia del Disegno under Cosimo I, at Vasari’s urging, which formalized this separation of conceiving and executing in training.

Quick clarity note. In that period disegno could mean a drawing and also a compositional scheme and several other things. It sat inside painting, sculpture, and architecture, so it does not map perfectly to how we use “design” today.

Some historians say the break is not that clean. Marta Ajmar argues that scholarship has often “overemphasized the separation between design and execution,” noting how workshop practice kept thinking close to materials and tools. Others point out that planning and execution were already split in parts of the Middle Ages. Master masons planned and directed teams, and the thirteenth-century Villard de Honnecourt portfolio shows plans, how-to notes, and geometric methods well before Alberti. Even within the sixteenth century the priority of disegno was not universal.

1750–1770: Industrial capitalism and the Wedgwood system

Some historians place the start of design in the second half of the eighteenth century, when making things for markets became a planned function inside industry. Adrian Forty in Objects of Desire (1986) puts the claim clearly: “design came into being at a particular stage in the history of capitalism and played a vital part in the creation of industrial wealth.” In this frame design is part of how factories decide what to make, how to make it, and how to sell it.

Josiah Wedgwood is the cleanest case study because his papers show the decisions in his own words. He set up his ceramics business in 1759. Ten years later he opened a purpose-built factory called Etruria in 1769. He set clear briefs and treated product development as a program. In his Experiment Book he wrote that he aimed “to try for some more solid improvements, as well as the body, as in the glazes, the colors & the forms of the articles of our manufacture.” He then focused on neoclassicism, hiring artists like John Flaxman to model reliefs for vases and plaques, the DNA of jasperware (fine-grained, unglazed stoneware developed by Josiah Wedgwood in the 1770s).

Wedgwood built repeatability. The factory ran on pattern books and shape numbers so teams could repeat forms and decorations across runs. He was blunt about hand painting, writing in 1769 that he would “rather … have to do with a shop of Potters than Painters,” because hand decoration was so inconsistent. To lock things down he adopted transfer printing, first through the Liverpool printers John Sadler and Guy Green and later brought printing in-house. When results varied he told the Liverpool printers he did not trust their “taste,” adding they had promised to “offtrace & coppy any prints … without attempting to mend or alter them.” The point was exact reproduction, not interpretation.

He also designed demand. After supplying Queen Charlotte in 1765 he named the line “Queen’s Ware,” telling his partner that “a name has a wonderful effect.” He was frank about the mechanics of taste: “Fashion is infinitely superior to merit.” Those are marketing rules written by a maker who knew how to place products and move volume.

Some scholars argue this is not the birth of design but a powerful phase in a longer craft-industry continuum. Holt and Popp read Wedgwood’s letters and experiments to show that craft knowledge was still central rather than being displaced by a distinct “design” function. Several elements pre-existed or were shared. Transfer printing came from Liverpool printers before Wedgwood used it. Furniture makers were already circulating designs via pattern books such as Chippendale’s Director (1754); and even Wedgwood innovations like pearlware look incremental when you scan the field.

1851, London: design reform after the Great Exhibition

Some historians say design begins when it becomes a modern reform effort. The date is 1851, London’s Great Exhibition. Writing decades later in Pioneers of Modern Design (1936), Nikolaus Pevsner argued that many exhibits showed “ignorance of that basic need in creating patterns, the integrity of the surface” and a “vulgarity in detail.” In his reading, the shock of 1851 makes the case for big reforms: standards, education and better models. You can check out the catalogue of the Great Exhibition of 1851 online.

The reforms are concrete. Henry Cole, a lead organizer of the Exhibition, helped found a Museum of Manufactures in 1852, with objects purchased from the show. That museum became the South Kensington Museum and later the Victoria and Albert Museum, with a clear mission: collect strong examples, teach with them, and raise the quality of British manufacture.

On the teaching side, reformers published manuals. Owen Jones issued The Grammar of Ornament in 1856, setting out principles for color, geometry, abstraction, and pattern. He also shaped teaching for the Government School of Design, the program that eventually became today’s Royal College of Art.

1851 is a trigger. It launches museums, manuals, and a system for teaching taste and method at scale. If you define the start of design as the moment a field names its problems in public and builds institutions to fix them, this might be the origin. Yes, British design education predates the Exhibition. The Government School of Design was founded in 1837, but it was drastically reshaped by the Exhibition era.

Alexandra Midal shifts both date and definition. She places the origin of design in 1841 with Catharine Beecher’s domestic manuals, where the kitchen and home are organized as systems to reduce women’s labor and advance a social program. Beecher writes that house planning should begin with the “economy of labor,” that every tool in the kitchen should have “a place appointed,” and that the day should be arranged to “promote systematic and habitual industry.” In this frame, “design” is not a museum-school response to bad goods in 1851. It is the intentional organization of everyday life a decade earlier, articulated in plans, workflows, and plain-language instructions.

Early 1900s. Design as a profession

Some historians mark the beginning of design when it becomes a named job inside industry. John Heskett is direct about the timing: “the profession of industrial designer emerged in the twentieth century,” as part of the growing division of labor in large-scale industry.

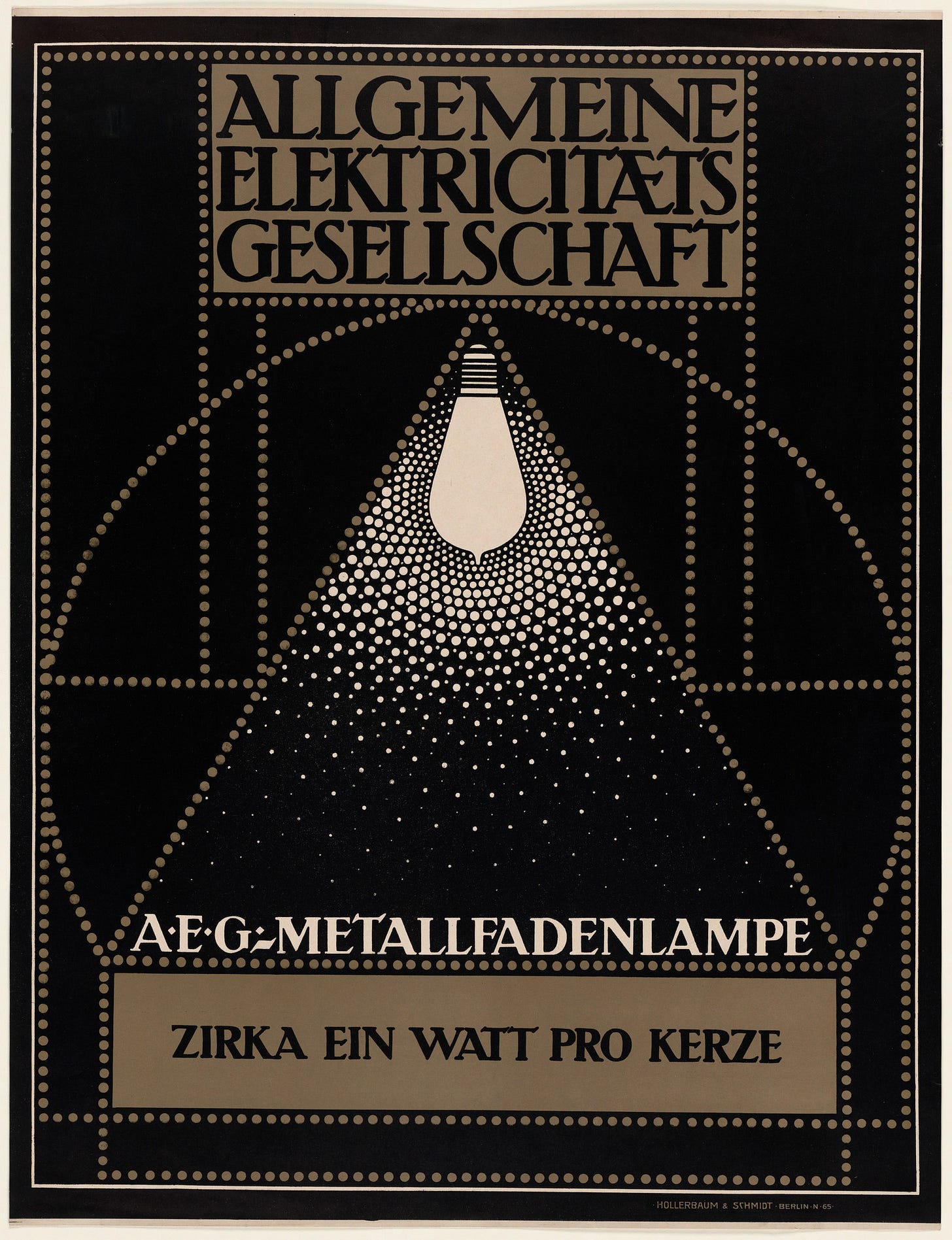

A clear European anchor is Peter Behrens at AEG, a major German electrical manufacturer founded in Berlin in 1883. In 1907 AEG hired Behrens as an artistic adviser. He coordinated company design in one place: products, advertising, graphics, the logotype, and even factory buildings.

At the same moment Germany created a wider platform. The Deutscher Werkbund, founded in 1907, was a national association of artists, artisans, architects, and industrialists. Its goal was to raise the standard of design for mass-produced goods and modern architecture by linking creative practice to industry.

In the United States the job solidified a little later. Jeffrey Meikle frames 1925–1939 as the window when the American industrial design profession takes shape, with named designers mediating between engineering, business, and users.

Taken together, this is the moment design becomes a career: titled roles, clear job descriptions, coordinated company programs, and networks that hire and train.

Design as a human activity

Some writers widen the lens and say there is no “start” at all. In this view design is what humans do when they plan and change things. Herbert Simon puts it in one line: “everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” Victor Papanek in Design for the Real World (1971) makes a similar claim: “All men are designers. All that we do, almost all the time, is design, for design is basic to all human activity.”

Victor Margolin’s World History of Design starts in prehistory and looks worldwide, not from any single exhibition or factory. The book’s scope is explicit: a “definitive” account of design “from prehistory to the end of the Second World War,” across regions and cultures.

Personally, this is my least favorite view. If everything we do, all the time, is design, then why even have a word for it? I write all day (emails, texts, comments). That does not make me a writer.

All in all, these are the most common “design birthdays” for design I’ve encountered in the literature over the years. To me, they feel like milestones rather than specific start dates for the profession. One thing had to happen before the next, and it took time for the concept of design to shift, take shape, and evolve into what it is today. In any case, I hope someone finds it helpful.

Sources:

Leon Battista Alberti. On the Art of Building, Prologue and Book 1 (1443–52).

Mario Carpo. Craftsman to Draftsman. The Albertian Paradigm and the Modern Invention of Construction Drawings (2013).

Cara Rachele. Seven Facets of Architectural Disegno.

Marta Ajmar. Mechanical Disegno (2014). From Special Issue “When Art History Meets Design History”.

Adrien Forty. Objects of Desire (1986).

Nikolaus Pevsner. Pioneers of Modern Design (1936).

Owen Jones. The grammar of Ornament (1856).

Alexandra Midal. Design by Accident (2019).

John Heskett. Industrial Design (1987).

Elizabeth M. Merrill. Peter Behrens, Turbine Factory.

Readymag special issue Peter Behrens. The first Designer

Jeffrey L. Meikle. Twentieth century limited : industrial design in America, 1925-1939 (1979)

Herbert A. Simon. The Science of Design: Creating the Artificial (1988)

Victor Papanek. Design for the Real World (1971).

I guess what he meant by "All men are designers, almost all the time" is that builders or creators do design... I had to look up the difference between planning and designing. Planning is setting the course, designing is creating the solution. So maybe the question is who was the first who thoughtfully created a solution to a problem?