Form (un)follows function

The Designer’s Chicken-and-Egg Dilemma.

If design were a religion, its first prophecy would be "Form follows function." As a designer, I’ve heard this mantra countless times, but I never really questioned its origins or context. I assumed it came from the Bauhaus or somewhere in that era. But form follows function isn’t just about design being dictated by purpose—it also implies that if form follows function, the result is inherently "good design." If not, it’s "bad design."

Where Did "Form Follows Function" Come From?

The phrase itself wasn’t born out of postwar manufacturing. It was first coined by Louis Sullivan in 1896 in his essay "The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered." Sullivan, a pioneer of modernist architecture, argued that a building’s form should be shaped by its function rather than by historical styles or unnecessary ornamentation.

But design historians argue that Sullivan wasn’t the originator of this idea. Horatio Greenough, an American sculptor and theorist, had already been making similar arguments 50 years earlier. His multiple essays, particularly "The Doctrine of Beauty" and "American Architecture," were compiled posthumously in 1852 in Form and Function: Remarks on Art, Design, and Architecture.

Greenough criticized architects for blindly imitating classical styles rather than designing with purpose. He believed that an object’s form should be determined by its function, not by tradition or excess ornamentation. He was particularly fascinated by fast ships of his time and wrote:

"The beauty of a ship or a flower lies in the economy of growth. Every stick of her timber is exactly where it is wanted. The shape of her bow is the shape that cleaves the water best.”

This illustrates his belief that functional needs should dictate design and beauty was equated with functionalism.

Design historian John Heskett offered a nuanced critique of the form follows function ideology in his book Industrial Design (1980). He argued that Greenough oversimplified the relationship between form and function, treating it as a direct cause-and-effect when in reality, multiple external factors—economic, political, and technological—shape design outcomes. My favorite critique relates to the very ships Greenough admired. He was obsessed with clippers—fast, early 19th-century sailing ships. Heskett writes:

The clipper ships were certainly among the most beautiful creations of their age, but Greenough tended to ignore the degree of scientific calculation that went to determining their form, and the particular functional objectives for which they were designed. They were built for the opium trade with China, in which speed was necessary to evade government patrols and pirates alike; … Calculations concerned with speed thus dictated the form of the hull, overriding optimum requirements for the inner working-structure and organization of the ship, and in this secondary area, function had to be adapted to form.

So, while the hull followed function (speed), everything else on the ship had to fit around the hull, meaning function had to follow the form.

Sir Henry Cole’s "Chamber of Horrors"

Interestingly, the debate around form and function was already active when Greenough was writing. In Designer, Maker, User, I read a fascinating story about Sir Henry Cole, a British designer and educator who played a key role in shaping design education and industrial innovation in the 19th century. His advocacy for practical, well-designed objects laid the groundwork for later movements.

In 1852 (the same year Greenough’s essays were published), Cole had a great idea! He set up a display at Marlborough House, London, to educate the public on "good design." He split the showroom into two sections:

"Good design" section: Featured carefully crafted items, including Kashmir shawls, Turkish knives, Tunisian pistols, floral wallpapers, and Axminster carpets.

"False Principles in Decoration" (nicknamed the "Chamber of Horrors") section: Displayed poor design examples like scissors shaped like a stork, a flowerpot imitating reeds, and an opal glass goblet, for which 'the transparency of the material was sacrificed to imitate alabaster'.

Charles Dickens mocked Cole’s museum in a December 1852 Household Words article, commissioning Henry Morley to write "A House Full of Horrors." The satire follows Mr. Crumpet of Brixton, who enjoys the exhibition—until he realizes it exposes his poor taste. Ironically, Cole admitted bad design attracted more interest than good, noting:

"This room appears to excite far greater interest than many objects of high excellence."

Frank Lloyd Wright: "Form and Function Are One"

Sullivan’s ideas later influenced Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), his student, who expanded the concept of form follows function into something more organic. Wright believed that form and function should exist in harmony, rather than one strictly dictating the other. His take:

"Form and function are one.”

However, critics argue that Wright often prioritized aesthetics over practicality. Many of his visually stunning buildings had leaky roofs, poor insulation, and impractical layouts. He was known for ignoring client needs and budgets to pursue his artistic vision. His Usonian homes, for instance, were expensive to maintain and lacked attics, basements, and storage space, frustrating homeowners.

It's ironic that Wright, despite being a student of the person who coined "form follows function," often swung dramatically in the opposite direction.

Le Corbusier’s Love for Ocean Liners

Le Corbusier (1887-1965) extended Sullivan’s philosophy to urban planning and architecture, famously stating:

"A house is a machine for living in."

Like Greenough, he praised the transatlantic liners as examples of pure functionalism. He admired the ships for their efficient use of space, high organization, functional zoning, and modern engineering, seeing them as a model for modernist architecture. In his book “Towards a New Architecture” of 1923, he added photographs of liners with enthusiastic captions, such as ‘An architecture pure, neat, clear, clean and healthy’.

Heskett, once again, challenged this idealized view of ships as pure functionalist design:

The great age of the liner began in the 1890s, and to many architects and designers, these ships were the epitome of the modern age: sleek, functional and beautiful. … However, the element of commercial and national rivalry led to the development of many features which cannot solely be explained in the terms of utility. The imposing superstructure built amidships, and the size and number of funnels, were deliberately designed to create a powerful impression of grandeur.

Many first-class areas on ocean liners were highly decorative, featuring Art Deco interiors, grand ballrooms, and elaborate lounges, directly contradicting the idea of pure functionalism. Even more striking, Titanic’s fourth funnel served no functional purpose at all—it was added purely for aesthetic balance and to create the illusion of greater power and speed. As Heskett points out, ocean liners were locked in fierce competition over speed, luxury, and grandeur. Ships were often equipped with additional funnels simply because they made the vessel appear more powerful and advanced—regardless of actual necessity.

Bauhaus and the Evolution of Functionalism

The idea of form follows function took center stage during the Bauhaus movement (1919–1933), which emerged in post-World War I Germany amid economic instability and industrial expansion. Founded by Walter Gropius, Bauhaus sought to reconcile art, craftsmanship, and modern industry, believing that design should serve society by being simple, functional, and accessible. Form follows function was not just a theory but a practical design approach that reflected the needs of its time, applied not only to architecture but also to furniture, typography, and product design.

A wealth of functional and beautiful artifacts emerged from Bauhaus, many of which designers still cherish today. But the movement was not without controversy. One of the more striking debates was over the elimination of capital letters.

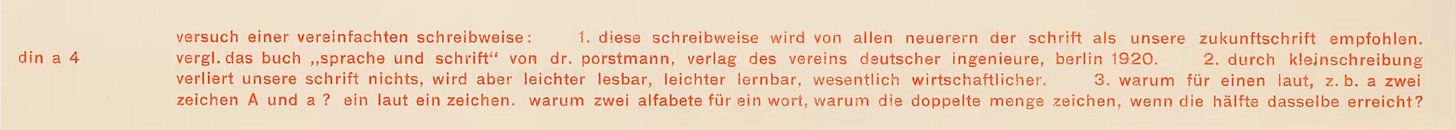

IIn 1920, German engineer Walter Porstmann published Sprache und Schrift (Speech and Writing), advocating for the exclusive use of lowercase letters—a practice known as Kleinschreibung. Porstmann argued that removing capital letters would enhance writing efficiency by simplifying typesetting, reducing the number of letterforms, and minimizing typographical errors. His reasoning was grounded in practicality and economy. He even acknowledged that capital letters serve as visual anchors in text but saw their benefit as minimal compared to the efficiency gains of a single-case system.

Porstmann's ideas resonated with Bauhaus designers, who embraced typographic simplifications as part of their broader design philosophy. Many took the lowercase-only concept to heart for two main reasons: one was technical efficiency (as Porstmann proposed), and the other was ideological. Bauhaus aimed to create a universal visual language, stripping away historical conventions they saw as arbitrary or elitist. Eliminating uppercase letters was viewed as a move toward democratization and accessibility, aligning with the school's ideals. By abolishing capital letters, they symbolically abolished unnecessary hierarchies.

In 1925, under the influence of designer Herbert Bayer, the Bauhaus school officially eliminated capital letters from its communications. Bayer convinced Walter Gropius to implement the change, reinforcing the school's principles of simplicity and functionality. The official Bauhaus letterhead proudly proclaimed:

we write everything in small letters, as we save time.

also: why 2 alphabets, if one achieves the same?

why capitalize, if you can't speak big?

One could argue for the rejection of superfluous hierarchies through lowercase-only writing. But the lack of capitalization created issues—proper names, last names, and geographical locations became harder to distinguish. Even designers of the time recognized that capital letters at the start of sentences improved readability by clearly marking where one thought ended and another began. This became an instance where form prevailed over function rather than following it.

Even Gropius, the Bauhaus director, agreed to the lowercase-only approach, but not without reservations. In a 1926 lecture, he described the fight against capital letters as a movement led by "extreme friends of standardization", referring to the change as "the hobbyhorse of pupils".

Here Comes Digital

In today’s digital age, many designers resist comparing digital products to physical ones. Yet, the notion of form follows function, originally rooted in designing physical artifacts, has seamlessly migrated into the digital space.

In the world of UI/UX design, Jakob Nielsen has been a major voice in advocating function-first principles. He famously stated:

"Users don’t care about design for its own sake. They just want to get things done and get out."

As I write this article on the Substack platform, a notification pops up with an exclamation mark (!) warning me: "Post too long for email"—a polite nudge to adapt my writing to whatever constraints the email system allows. But I dismiss the notification and continue writing because I refuse to shape my form to fit this arbitrary function. 😂

The hard truth is that digital designers have to follow form far more often than one might think—and not in the way Nielsen suggests. Having designed digital experiences for over 20 years, I’ve lost count of how many times clients and organizations have been shackled by outdated infrastructure and legacy databases that someone set up years ago and are now too expensive to overhaul. Whether it’s a media publication, a financial institution, an airline, or a museum—any organization that has existed for years has its own legacy "monster" that everyone is afraid to touch.

In these cases, whether you like it or not, designers are often forced to follow the functions dictated by the constraints of these set in stone legacy systems—much like how 19th-century engineers had to fit the inner workings of a clipper ship into its narrow hull. Yes, there are workarounds, ways to build on top of a system that doesn’t support the features you want—but these solutions come at a cost, adding complexity to everything. You get the idea.

In no way did I write this article to critique minds far greater than my own. Despite the contradictions in the form follows function mantra, every figure mentioned here played a crucial role in shaping the world we live in and inspiring generations of designers, architects, and artists.

My curiosity about this topic wasn’t to challenge these principles but to explore their origins and evolution. The ongoing debates about form and function that we engage in today are far from new. History has shown that pure functionalism doesn’t always hold up. Whether in ships, buildings, or everyday objects, function is often shaped by cultural, aesthetic, and economic forces. Even designers who strongly adhered to form follows function—such as Max Bill—acknowledged this reality, proving that design is rarely as rigid or absolute as theory suggests.

References:

Sullivan, L. (1896). The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered.

Greenough, Horatio (1852). Form and Function

Heskett, John (1980). Industrial Design.

Le Corbusier (1923). Toward a New Architecture.

Porstmann, Walter (1920). Sprache und Schrift

Newson, Alex (Design Museum) (2017). Designer Maker User

Mijksenaar, Paul (1997). Visual Function