Love your tools

Get a pen that you love, and you'll find yourself always writing.

Quite often, I hear photographers say that the gear is not important for capturing great photos; it's all about how you take pictures. This is true to some degree. You can potentially use any type of camera to get a great shot one way or another. But in my case, the gear is super important. It’s not about the megapixels, the brand, or having the latest and most robust version of the camera. It’s about having a camera you genuinely enjoy using.

I believe it's better to have a camera that you love as an object. You like how it feels in your hand, and the grip feels just right for you. Its controls make sense; pressing buttons, changing aperture, and adjusting shutter speed all feel intuitive. Just using this object gives you pleasure. Over time, you develop a "feel" for the camera and how it reacts to different lighting conditions, to the point where you do not rely on automatic settings. It’s a camera that you want to always have with you and use all the time. If you own a camera like this, there's a high chance you'll always have it with you and frequently use it, ultimately increasing the likelihood of capturing great photos. It doesn’t matter if it’s a Leica, an old film Canon, a medium format Hasselblad, or an iPhone—as long as it's a camera that you love.

I remember going on a trip once with a brand new camera that boasted all the megapixels in the world. It was the latest and greatest model the camera store had to offer. However, I rarely used it because I didn't enjoy using it. Something—or rather, everything—felt off about the camera. It just didn't feel right. Each time I went for a walk, I left it behind because I didn’t feel like taking photos. I regretted not bringing my older camera that I loved, because I knew I would have taken it with me everywhere and ended up with much better shots.

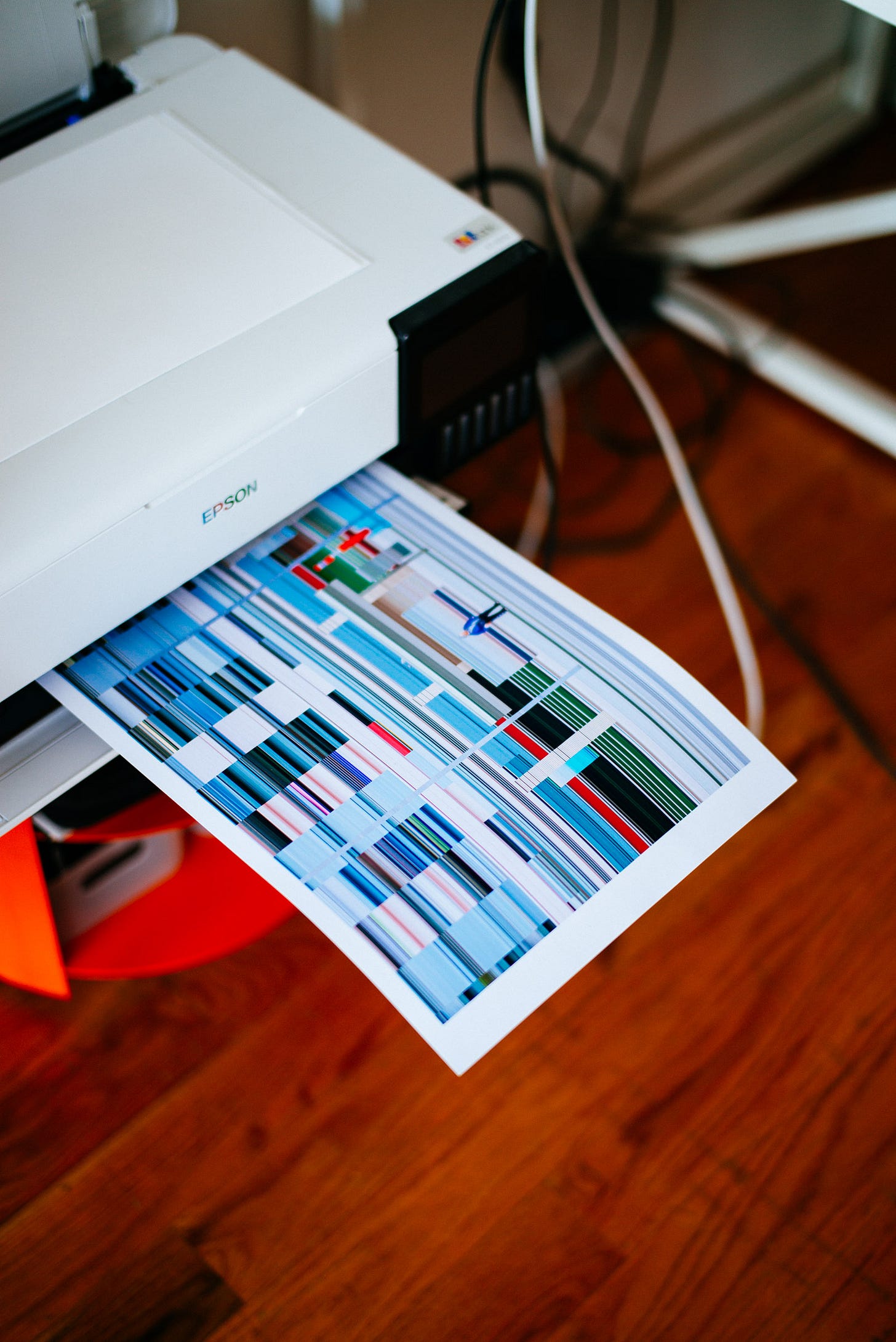

For me, gear is not just important; it's a huge source of inspiration. I have a friend who feels the same way. He once told me he bought a second-hand plotter, even though he had no idea how he would use it or how often. Just having the plotter opened up possibilities for ideas that necessitated one. I completely understand that feeling.

Last year, I bought a printer. While I occasionally needed to print documents or shipping slips, which was always a hassle, I opted for a larger color printer instead of a small black-and-white one. This decision opened up new possibilities for me. I started printing books and artoworks, and found myself constantly coming up with ideas for them. This is one of the reasons the Time Stretched, an ongoing project I am invested in since 2022 was even born.

And it didn't stop there. With this new capability "unlocked," I kept coming up with projects to print. While not all of them were great, each one led to something else and sparked new ideas that I later worked on.

Yes, tools can be expensive, and I can't afford some of the things I want. However, there's also the second-hand market. In the US, this means Craigslist or Facebook Marketplace. I buy most of my tools, including cameras and lenses, second hand. Some things don't have to be brand new. And once a tool is no longer inspiring for you, sell it and pass that inspiration on to someone else.

Get a pen that you love, and you'll find yourself always writing.

Inspiring tools can also be digital. Several years ago, I discovered Notion, which inspired me to document my process more, record ideas, and organize them. I began writing down things I liked and why. The fact that I am writing this story right now is largely because many of these ideas originated from my notes in Notion.

Here's a short story, that I find very inspiring, about a digital tool that helped make Frank Gehry the star architect he is today. If you've ever been to Barcelona, you probably noticed the large "fish" (El Peix) structure in the Olympic Marina right on the beach.

Back in the early '90s, in preparation for the 1992 Olympics, the marina was completely rebuilt. Frank Gehry, who was not yet a star architect at that time, was commissioned to design a sculpture that would reflect the city's Mediterranean and maritime identity. The main challenge was creating technical drawings for the "streamlined" (curved) design Gehry envisioned.

Before computers, accurately annotating streamlined curves by hand was a daunting task. Imagine the number of points needed in three dimensions—X, Y, and Z—to describe such a shape. It would take an enormous amount of time to produce each section with detailed notations for every point, ensuring a smooth curve when finally built. If a person couldn't do that in a reasonable amount of time, maybe a software could.

Frank Gehry's office contacted McDonnell Douglas, a US plane manufacturer known for using 3D software to design and specify streamlined surfaces, like airplane wings. However, this lead didn't pan out. A friend of Gehry's, the head of architecture at MIT, connected him with Dassault, a plane manufacturer in Paris that used their own 3D software called CATIA to design Mirage fighter jets.

CATIA was the very first CAD/CAE/CAM software created back in 1977 as a surface modeler to assist in designing the Dassault fighter jets. It could theoretically solve Gehry's problem: preparing technical drawings using splines in 3D for streamlined architectural surfaces. The catch was that the software was so complex and not user-friendly, only Dassault engineers could use it. After some convincing, Dassault agreed to simplify the software and adapt it for architectural purposes. This allowed Frank Gehry to design and build "The Fish," which became renowned for its innovative design achieved using 3D software. Something that nobody has ever done before.

Gehry liked the software so much that he copyrighted the simplified version of CATIA for architecture, calling it "Digital Project". He founded a separate company, Gehry Technologies, to distribute the "Digital Project" software to other architectural firms needing spline modeling. He used the same software to design the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao in 1996 and in all his subsequent projects.

This story is significant because technology, particularly software, defined Frank Gehry's career as an architect. Of course, he was a talented architect, but his career might have been completely different if he hadn't discovered that software and become so invested in it. The software enabled him to create the curved facades of so many buildings he designed. It’s a story where software is a defining element not only of someone's success but of their style itself.

Love your tools.

I was gifted an upgraded sewing machine for Christmas to replace the machine I've had for a decade. It took half an hour to thread, couldn't hold tension, and skipped every other stitch. I've already completed more projects, of much higher quality, than I did in the last year or even two with my old machine. I love and use it and have already discovered fun new capabilities that change my project's potential. Love your tools, love what they help you make.