Touching Digital

Rediscovering the Joy of Tactile Interactions

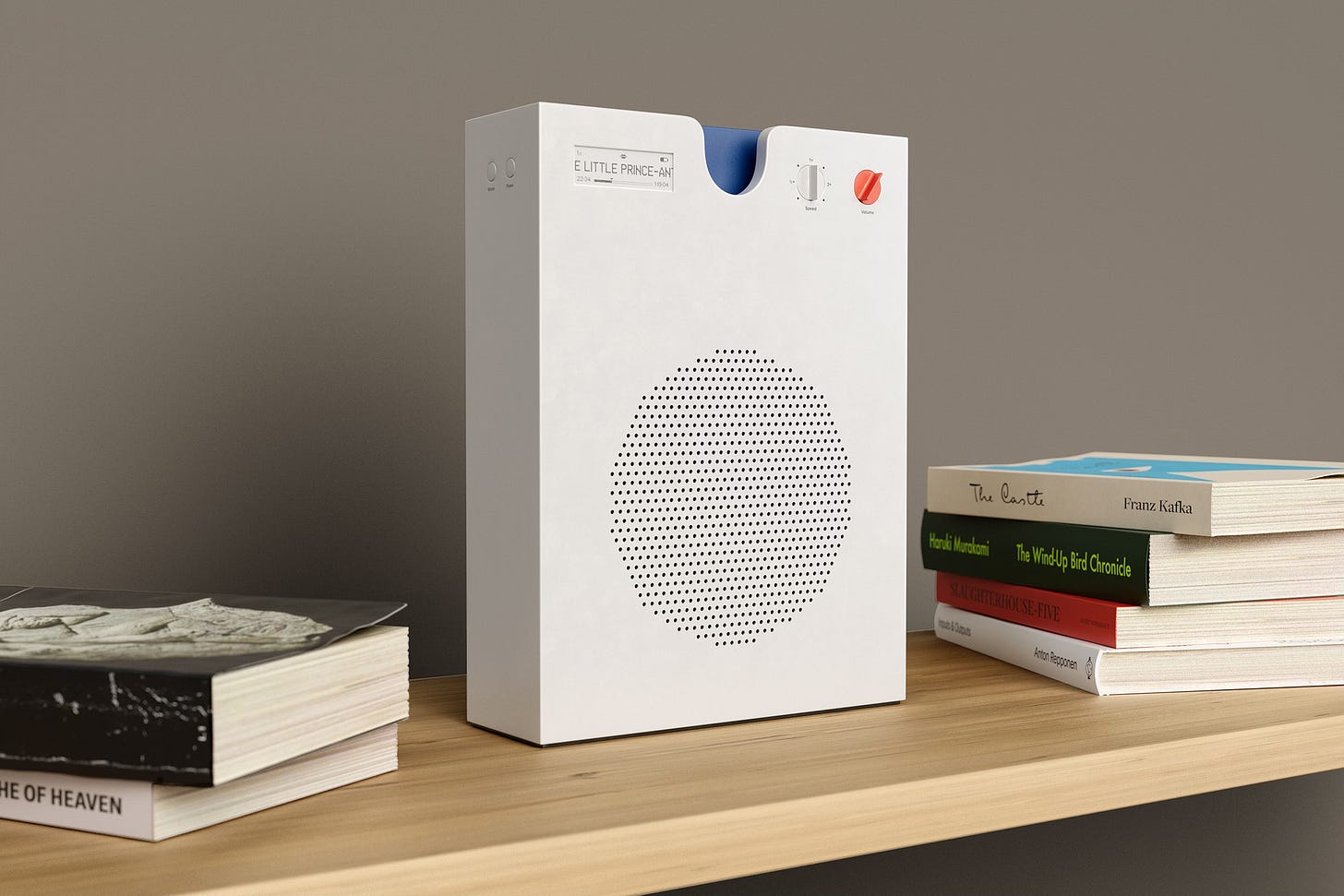

About two months ago, I envisioned a speaker that could read aloud a physical book you already own when you place it inside the device. Over a weekend, I visualized the concept and shared it online. I’m not an industrial designer, nor am I in the business of creating new services. This was purely an exploration, driven by curiosity about whether interactions with digital products can feel more tactile. That’s all there is to it. The idea is simple: you take a book from your shelf, place it into the device, and it "recognizes" the book, then begins reading it to you. Would this require a subscription or access to audiobook services? Maybe, maybe not—that’s beside the point. The focus here is solely on testing the interaction with technology.

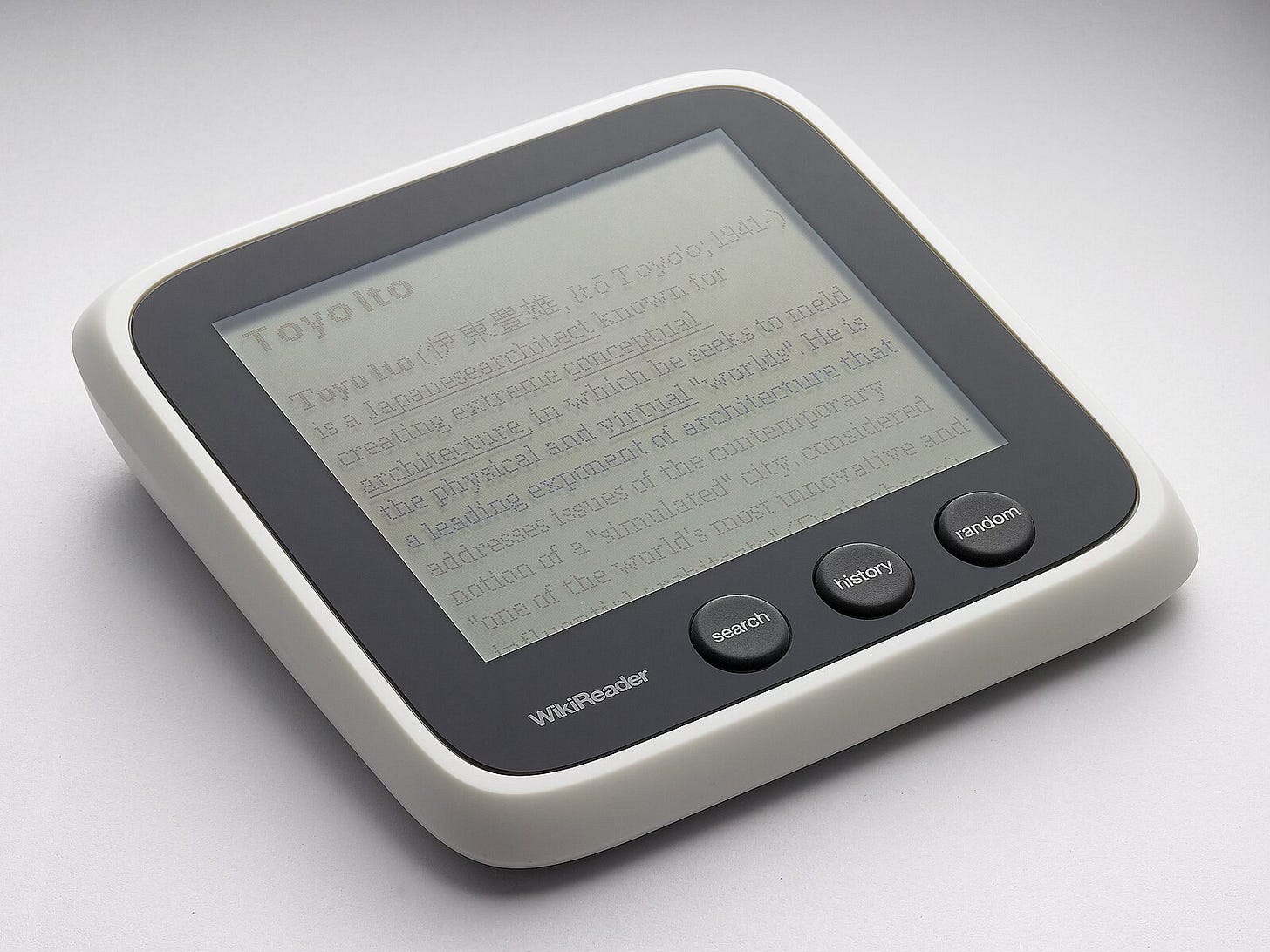

The motivation behind this concept stems from my sense that digital products have become too similar. Booking a hotel, for instance, feels visually and interactively no different from checking a bank account—and there’s a clear reason for this. Tasks that once required dedicated hardware are now condensed into apps on a single smartphone. Before the era of smartphones and apps, every piece of technology had its own dedicated device. Need to do math? You’d use a calculator. Want to listen to music on the go? You’d grab a Walkman. Taking photos? You’d reach for a camera. Recently, I even discovered that Wikipedia had its own standalone device called the WikiReader, released in 2009 and discontinued in 2014.

Let me be clear: I’m not advocating for a return to having a separate gadget for every task. Owning ten devices to perform ten functions feels impractical today—and it’s far from environmentally friendly. However, it’s also disheartening that just two smartphone companies largely dictate how we interact with nearly every digital service available. Remember the phrase “form follows function”? We seem to be doing the opposite now. The form—defined by Apple or Google—dictates the function, and we cram every imaginable feature into their predefined shapes. Smartphones have become a "one-size-fits-all" device, and with the prevalence of "best practices," few companies dare to break away from this mold.

Last year, we caught a glimpse of efforts to rethink how we interact with technology, particularly with the emergence of AI. Take, for example, the much-discussed Humane Pin and Rabbit R1. While both were criticized for overpromising and underdelivering, the most common public reaction was, “This could have been an app.” And yes, perhaps it could have. But I still credit both companies for at least daring to look in a different direction, exploring whether there might be something more beyond the app-centric status quo.

When thinking about making digital interactions more tactile, two examples come to mind that I found particularly compelling. One is a concept called Tiles, created by designers Kay van den Aker, Oscar Olsson, Emile Chuffart, and Tobias Ertel. Their work explored how a tangible interface could transform music listening into the rich, sophisticated experience it was meant to be.

Another example I greatly enjoyed is Lazy Pen by Nicolas Nahornyj. When we type on digital devices, our writing appears uniform, but when we use pens, our handwriting is uniquely our own. This project is a practical attempt to merge the individuality of handwriting with computer-based word processing. A moving palette under the user’s wrist captures arm movements and pressure, distorting the font while typing. As a result, two people typing on the same device produce distinct outputs. Personal movements and habits shape the typography, creating a unique, individualized writing style.

The truth is, there are countless physical products I genuinely enjoy using, but I can’t say the same about digital ones. While some digital products solve immediate problems, they rarely inspire any real affection and I have absolutely zero desire using any of them. For example, I’m perfectly fine listening to music on Spotify, but I also own a record player and regularly buy records I love. Why? Because the interaction required to play a vinyl album offers something unique—a tangible, deliberate experience that digital platforms stay away from. To me, that interaction has value. I also believe that people, when exposed to more tactile interactions, often respond positively. I don’t own AR glasses, but I completely understand their appeal. They bring a more tactile, physical dimension to engaging with digital technologies, and that resonates with people.

Returning to the Audio Book Speaker concept, I posted it on social media and received responses that were largely expected. Most people felt content with the audiobook apps already installed on their phones and dismissed the device as unnecessary. On some level, I don’t disagree. Many also compared it to Yoto, a small speaker for kids that I had come across before—primarily because Pentagram handled its branding—but had long forgotten about. While both concepts are standalone speakers for audiobooks, my idea differs in that it relies on physical books you already own, sitting on your shelf, rather than purchasing customized cartridges. Interestingly, a smaller group of people liked the concept, and a few even reached out, expressing interest in prototyping it.

Another concept I explored in 2019 wasn’t strictly a digital product but still examined the interaction between humans and devices. Called the Stick Lamp, it was a portable lamp inspired by the ancient ritual of rubbing wooden sticks to create fire.

To light it, you’d rub the stick with both hands—the longer you rubbed, the longer it stayed on. To turn it off, you’d simply hold the stick as if extinguishing a flame. The idea was to merge tactile interaction with a playful nod to tradition, creating a functional object that felt both intuitive and symbolic.

The journey of exploring tactile interactions with digital products is less about replacing what works and more about imagining what could be. Physical, tactile interactions can offer a richness and depth that digital interfaces often lack—a way to connect with our devices that feels more human. As technology continues to evolve, we shouldn’t be afraid to question the dominance of screens and uniformity. Whether it’s through reimagining everyday tasks or experimenting with alternative forms of interaction, there’s value in exploring paths that stray from the well-worn “best practices.” In a world of endless apps and identical interactions, perhaps the answer lies in creating digital products that we not only use but love—because they touch us in ways that go beyond the screen.

If you know of any great examples of interactions like these, I’d love to see them—please send them my way!

Recently I've seen this product called Dot card. They made a bracelet that you can tap your phone to and it works like a virtual business card. I feel like it would be cool for a career fair or some sort of business group. I think the main problem with hardware is that so many things are case by case usesage. Like I wouldn't wear my dot card band to my Bible study. but at the same time one of the best things I've liked about hardware (although this seems to be changing a good bit too) is that typically they didn't require a subscription but now of course companies like Whoop, ōura and other fitness trackers specifically do require subscription.

Also for not being an industrial designer your book reader idea still came out really cool. I like the color and design of it. I wonder how it would know what book it is that your inserting? Maybe some sort of barcode reader at the bottom!